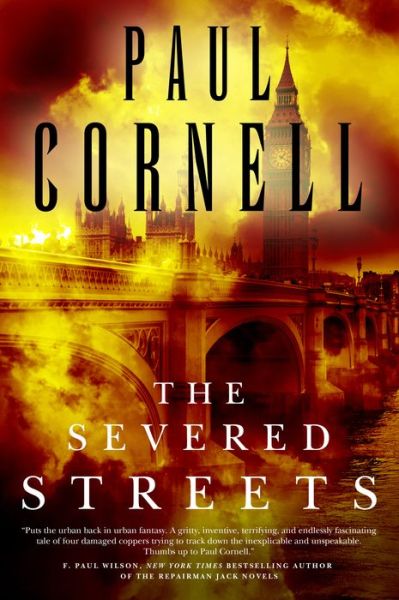

Detective Inspector James Quill is back in Paul Cornell’s The Severed Streets—a police procedural tinged with fantasy—available May 20th from Tor Books!

Desperate to find a case to justify the team’s existence, with budget cuts and a police strike on the horizon, Quill thinks he’s struck gold when a cabinet minister is murdered by an assailant who wasn’t seen getting in or out of his limo. A second murder, that of the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, presents a crime scene with a message identical to that left by the original Jack the Ripper.

The new Ripper seems to have changed the MO of the old completely: he’s only killing rich white men. The inquiry into just what this supernatural menace is takes Quill and his team into the corridors of power at Whitehall, to meetings with MI5, or ‘the funny people’ as the Met call them, and into the London occult underworld. They go undercover to a pub with a regular evening that caters to that clientele, and to an auction of objects of power at the Tate Modern.

ONE

Detective Inspector James Quill liked his sleep. He liked it especially on these short summer nights when he was woken by the dawn and had had to leave the window open to get cool, and then it rained on the carpet. He would only willingly give up his sleep for his daughter, Jessica, who would on occasion wander into his and Sarah’s bedroom at 3 a.m. with something very important to tell them. These days Quill, having once been made to forget Jessica through occult means, would listen to that important thing with a bit more patience. Now once again there was an unusual noise in his bedroom, and he found a smile coming to his face, sure it was her.

He blinked awake, realizing that this time the noise wasn’t the voice of his child, but of his phone on the bedside table, ringing.

He lay there for a moment. There was a lovely pre-dawn light through the curtains.

‘Would you please answer that,’ said Sarah, ‘and tell them to fuck off?’

Quill saw who was calling and answered the phone. ‘Lisa Ross,’ he said, ‘my wife sends you her fondest regards.’

‘If it’s her, I actually do,’ amended Sarah.

‘It’s the Michael Spatley murder, Jimmy.’ The intelligence analyst’s voice on the other end of the line sounded excited.

‘Please don’t tell me—?’

‘Yeah. It looks like this is one of ours.’

Quill took a deep breath as he always did before quietly opening the door of his semi-detached in Enfield and stepping out into the world. He looked around cautiously as he approached his car in the driveway. This morning there didn’t seem to be anything horrifying—

‘Morning,’ said a voice from nearby.

Quill jumped. He looked round, his heart racing.

It was the newspaper delivery guy, with a bag over his shoulder. He’d parked his van at the end of the close. Quill tried to make himself give the bloke a smile, but he’d already seen what was with him. The delivery guy was followed by a trail of small figures, giggling and nudging each other. They looked like tiny monks and wore robes that hid their faces. As Quill watched, one of them, seemingly unnoticed by the man, leaped up like a monkey onto his shoulder and whispered something in his ear. The man’s expression remained unchanged. But now Quill thought he could see a burden in the eyes, something being gnawed at. ‘Don’t like the look of the news this morning,’ said the man, his voice a monotone.

Quill nodded and went swiftly to unlock his car.

He headed for the A10, but, as always, couldn’t help but look up into the sky ahead of him as he did so. Towards the reservoir, something horrifying loomed in the air. It was there every day. It had taken him a while to notice it, as was the way with the Sight—the ability to see and feel the hidden things of London that he and his team of police officers had acquired by accident less than six months ago. Once he had seen the thing, it had become more and more obvious, to the point where he now wished he could ignore it.

But, being a copper, every time he had to look.

It was a vortex of smashed crockery, broken furniture, all the cared-for items of a home, whirling and breaking above a particular house somewhere over there, over and over again, each beloved thing impossibly fixing itself only to be smashed again. He could never see such detail from the car, obviously, but as he’d become aware of it, he’d gained the emotional context, the feeling of rage and betrayal, the horrible intimacy of it. Those feelings were also part of what the Sight did. The detail of what he was seeing had come when he’d looked into the matter and found out about a poltergeist case that dated back to the seventies. Once he knew what he was looking at, the Sight had filled in the gaps, and now every time he drove this way he was therefore burdened by something that looked like a distant weather phenomenon but also shouted pain into his face.

The worst thing of all was that there was nothing he could do about it. The participants no longer lived around here. No crime that he was aware of had been committed. It might not even have really happened. But in some way, via some mechanism that he and his team had not yet got to grips with, London remembered it. Being remembered was one of the two ways one could gain power from some intrinsic property of the metropolis itself; the other being to make an awful sacrifice to… well, they didn’t know what the sacrifice was made to, really, though they had made some worrying guesses. Quill sometimes thought that living here with the Sight was like continually wearing those Google glasses he’d read about—always seeing notations about the world. Except in this case the notes were all about ancient pain and horror.

Those little buggers in the hoods were another example. As far as he and the others could tell, they were some sort of… well, they were either a metaphorical representation of various psychiatric disorders—of human misery, basically—or they actually were that misery, and psychiatry was the metaphor. They were as common as rats, and Quill’s team had quickly stopped trying to deal with every instance of them they saw in the street. They could be chased away, or the person they were tormenting could be taken away from them, but they always came back. Quill could swear that, as the summer came on, he was seeing more and more of them. At least he didn’t have any following him. Yet.

He turned the car onto the A10, thankful not to have the weight of that poltergeist thing in the sky right in front of him any more. The familiar lit-up suburban bulk of the lightbulb factory loomed ahead; a few early cars were on the road. He took comfort in the ordinary these days. He switched on the radio, found some music on Radio 2. He felt guilty every time he thought about it, but he often found himself wondering if life would have been so bad had he and his team actually accepted the offer that had been made to them. That terrifying bastard whom they called the ‘Smiling Man’, who was almost certainly not a man at all, had used a proxy to tell them that he was willing to take away the Sight. They, being coppers, being aware that if they did that they’d spend the rest of their lives wondering what they were missing when they came across a crime scene with some hidden dimension, being aware that that smiling bastard who had been behind their first case had something enormous planned… like mugs they had all, for their differing reasons, said no.

It didn’t help that the awful things they could all now see were confined to London. You could get away from it by going on a day trip to Reading. Quill and Sarah had taken Jessica to a theme park in the Midlands a couple of weekends ago, and had had what had felt like the best sleep of their lives. Sarah didn’t share the Sight. She hadn’t been there when Quill had touched that pile of soil in the house of serial killer—and, as it turned out, wicked witch—Mora Losley. In some way that they still didn’t understand, it had been that action that activated this ability in himself and his three nearby colleagues. Sarah only knew what Quill told her, which was just about everything. On the drive back to London from their weekend break, Quill had seen Sarah’s expression, how complicated it was. She was trying to hide the fact that she admired Quill’s need to do his duty… but hated it too.

Quill realized that the radio was playing ‘London Calling’ by the Clash and angrily changed the channel to Classic FM. He didn’t need his situation underlining, thank you very much. He wound down the window and immediately regretted it, but left it open for the cool air on his face. The air brought with it the smell of burning. The smell was of last night’s riots and lootings, of some borough or other going up in smoke. Thanks to an interesting series of interactions between this government and certain classes of the general public, it was shaping up to be one of those summers. He and his team had been told that the Smiling Man had a ‘process’ that he was ‘putting together’, and Quill kept wondering if he was somewhere behind the violence. He could imagine a reality where the coalition in power had done a lot of the same shit, but without a response that included Londoners burning down their own communities. Really, it was down to how the initial outbreaks of violence had been mismanaged and a strained relationship between government and the Met that was leaving him increasingly incredulous.

The news came on the radio, and he made himself listen. Sporadic looting, protests against the cuts and austerity measures. Cars on fire and bottles being thrown at police. ‘The postal ballot on strike action by the Police Federation—’

Quill told the radio to piss off as he changed the channel again. He could understand the frustration felt by his fellow officers, really he could. Every move, every sensible decision that the Met made to get to the cause of the unrest and damp it down seemed to be instantly overturned and criticized by either the mayor’s office or the Home Office. To the ‘lid’, the uniformed police officer on the street, what that meant was that you got spit in your face and then found out that you were going back the next night for more of exactly the same, when it was obvious to you and your mates—spread out and targets for missiles as you were—that the situation wasn’t going to get any better. The other police forces of Britain had their own difficult relations with this government, knew where the Met was coming from and wanted to support their colleagues.

But strike action? His old police dad, Marty, had been on the phone from Essex, making sure Quill wasn’t having any of that. It was against all the traditions of the Met. Against the law, even—coppers didn’t have the right. Besides, Quill’s team’s speciality, standing against the powers of darkness, seemed a bit too urgent to allow for industrial action.

He realized he was passing the cemetery on his right. He always tried not to glance over there, and always failed. Graveyards were usually, in his team’s experience, a bad idea. This one was full of greenish lights that danced between the graves, and there were a couple of swaying figures, one an emaciated husk with glowing eyes who had taken to… yes, there he was again this morning, like every morning.

Quill tiredly raised his hand to return the wave.

Forty minutes later, Quill got out of his car at Belgravia police station. The sky was getting properly light now. He found Ross standing under one of the big fluorescent car park lights, moths fluttering around it. She had been watching the first batch of last night’s Toff protestors, the ones whom the police presumably had no legal reason to keep, stumbling from the building. They had those Halloweenstyle costumes of theirs bundled under their arms. A few of them were, even now, giving each other high fives and laughing. But most of them looked grim. Quill looked at their emotion and again felt distant copper annoyance at bloody people. He used to joke that without people his job would be a lot easier. But now he supposed he couldn’t even say that. ‘What have we got?’ he asked.

She looked round at him. Maybe she was his team’s intelligence analyst, a civilian, but what they’d been through together had brought them as close as Quill had ever felt to any fellow officer. He owed her the life of his child. There was something about the paleness of Ross’ left eye compared to her right, about the broken angle of her nose, that made it always look as if she’d just been in a fight. Her hair was cut short to the point where sometimes it looked as if she’d just taken a razor to it. She was biting her bottom lip in that skewed smile of hers, which only appeared once in a blue moon, and which Quill had started to associate with the game, as they say, being afoot. ‘Maybe just the op we’ve been looking for,’ she said.

Quill had caught up with the Spatley case before he’d left the house. The headline on the first edition of the Herald had read, ‘Murdered by the Mob’. Michael Spatley, chief secretary to the Treasury, had been cornered in his car by anti-government protestors, who had forced their way in and eviscerated him. The story had been the lead on the BBC ten o’clock bulletin last night, but Quill had gone to bed thinking, ironically, that he was glad that it wasn’t his problem.

‘Why is it one of ours?’

Ross led him towards the doors of the nick. ‘I have search strings set up in the Crime Reporting Information System, and I check them four times a day. A locked report came through on my page of results late last night, with the heading directing me to the extension of one DCI Jason Forrest. I couldn’t read it, but if it set off my searches it must contain some extreme words, like “impossible”. Around 2 a.m. it showed up on the Home Office Large Major Enquiry System too, so it’s a murder. I checked where this bloke Forrest works, and it’s this nick, which is also the obvious one for a suspect in the Spatley case to be brought back to. I got excited and called you.’

Quill wanted to slap her on the shoulder or fist-bump her or something, but the very urge was against his copper nature. His was a squad created within the budget of a detective superintendent, its objectives hidden from the mainstream of the Metropolitan Police while cut after cut reduced the operational capacity of every other Met department, and the riots and the protests and the outbursts of dissent in the force’s own ranks were pushing the system to breaking point. His team needed a new target nominal—a new operation—before people in senior positions started asking questions about why they existed.

‘And you were awake at 2 a.m. because… ?’

Her poker face was immediately back. Quill sighed to see it. After they’d defeated Mora Losley and thus solved the mystery that had loomed over Ross for her whole life, the analyst had opened up for a few weeks, become more talkative, cracked a few jokes, even. It had been wonderful to see. But now the cloud was back. ‘I’m still working through those documents we found in the ruins in Docklands.’

She was also, thought Quill, probably still considering the plight of her deceased dad, who, in the course of the team’s first—and so far only—op, she’d discovered to be residing in Hell. Whatever Hell was. Quill was pretty sure it didn’t map onto conventional thoughts about damnation. Ross had told them that she was aiming, in the fullness of time, to do something about getting her dad out of there, if they ever found a mechanism to do so. Whether or not she’d made any progress on that was between her and her copious notebooks. ‘Okay, but—’

‘That’s my own time, Jimmy.’

Quill raised his hands in surrender, and indicated for her to proceed.

‘Witnesses are saying to the press that the doors of the car weren’t opened at any point, meaning that the government service driver, whom I’ve discovered was one Brian Tunstall, must be the only suspect, presumably the “thirty-eight-year-old male” the Major Investigation Team have announced they’ve arrested in connection. The words that set off my searches might well be contained in his interview statement.’

‘Terrific.’ Quill took out his phone. ‘You get our two comrades over here. I am about to wake a detective superintendent.’

The first result of Quill’s call to his superior was that a hassledlooking lid came out of the nick, found Quill and Ross, and checked them through into the canteen. As in any nick, the canteen smelt of comforting grease and echoed with the clatter of cutlery and the sound of music radio from the kitchens. To venture any further into this bureaucracy, they were going to need their political muscle here with them. The food hall was full of uniforms looking pissed off, having just come off a shift where half of them would have been beaten on by protestors and rioters. Ross kept looking at her phone. ‘Now they’ve made an arrest, I’m waiting for those “the mob did it” stories on the news websites to change. They might give us more information to go on.’

‘In the meantime,’ said Quill, ‘there exist in this world bacon sarnies.’

Forty-five minutes later, Kev Sefton arrived, dressed like his undercover self, in hoodie and trainers, but with the holdall he now carried everywhere. Quill suspected that, given the riots, the detective constable must have been stopped a few times lately and searched for the crime of being black in the wrong suburb. Quill just hoped Sefton flashed his warrant card before the uniforms found the collection of occult, or what they’d taken to simply calling ‘London’, items that he now regularly carried in that holdall. In their line of work, as Sefton had discovered, some ancient horse brass with a provenance in the metropolis could be much handier in terms of repelling evil than garlic. If Ross had a boxer’s nose, Sefton had the rest of that body shape, compact and hard. As Quill had discovered, what went with that physique was a detective’s intellect that was willing to believe in extraordinary possibilities, which could lead Sefton to think about the horrifying reality they’d discovered—to a degree that the rest of the team, Quill included, weren’t yet capable of. It was as if he had an undercover officer’s adaptability that could extend itself beyond reality. Quill had started to think of him as his weird-London-shit officer. He got the feeling that that role was letting Sefton breathe, that all his life he’d been waiting for a chance like this.

‘I thought this might be one of ours,’ he said, sitting down.

‘Do you mean that you did some sort of… ?’ Quill still didn’t have the language to form that kind of question, so he contented himself with spreading his hands like a stage illusionist, indicating the sort of occult London thing that he supposed Sefton now did.

‘I wish I had some sort of…’ Sefton returned the gesture with a smile.

Quill was pleased to see that. He knew that Sefton liked to try and keep a positive surface going, but that being the one to deal with the London shit, especially when they’d made relatively little progress, weighed heavily on him. He had had adventures on his own that, while he’d described them to the team in every possible detail, he’d added had been like ‘something out of a dream’. Which wasn’t your normal copper description of encountering a potential informant.

‘Right then!’ That was Tony Costain, marching in as if he owned the place as always, dressed to the nines as always, in a retro leather coat that emphasized his tall, slim loomingness. The detective sergeant was the other black former undercover police officer on the team. If Costain smiled at you, and you knew who he really was, you wondered what he was hiding, because here was a copper who’d been willing to sell on drugs and guns he’d nicked from the gang he’d been undercover in. Still, Quill felt he’d treated Costain too roughly on occasion. He had felt for Costain when he’d developed a desperate desire not to go to Hell and had decided that from now on he was going to clean up his act, having caught a glimpse of the Hell he was certain was waiting for him. It felt like something that didn’t sit well with the man, though: an abstinence that chafed on him every day. Costain, basically, didn’t want to be a good boy. Quill had never said it out loud, but he’d started to think of this consummate actor’s ability to step in and out of the dark side, to bring on the dodgy stuff, as a positive asset to the team. He had found himself hoping that, should push come to shove, Costain could find it in himself to do, perhaps, extreme violence and leave redemption until later. ‘You look like you got some sleep,’ he said.

‘The sleep of the just,’ Costain nodded.

‘The just what?’

Costain gave Quill exactly the sort of smile he’d been anticipating.

‘There you are, James, with the bacon sarnies.’ Detective Superintendent Lofthouse had entered. The smart, angular middleaged woman looked exhausted, as always, while never actually seeming tired. ‘Someone’s fetching one for me, and a gallon of coffee to go with it.’ She sat down with them and lowered her voice. ‘I’ve had a word with the senior investigating officer on the Spatley case, Jason Forrest, and he, despite his puzzlement, you will be pleased to hear, has expressed his trust in his old mate, me, by asking to talk to you at the earliest opportunity. You and I are to take the lift to the third floor.’

‘Thank you, ma’am.’ Quill found himself sitting straighter in his chair and glanced around at his team to see them all reacting similarly. None of them quite knew how to deal with their boss these days.

Three months ago, Quill’s team had used a pair of ‘vanes’ that had been employed to attack Quill with some sort of weaponized poltergeist but could also be utilized as dowsing equipment. With these they had found a ruined building in London’s Docklands. It was something like a temple, the remains standing absurdly on an open space between office blocks by the river. There had been ornate chairs and a big marble table that had been cracked in two. A pentagram had been inscribed on both that table and the ground underneath. Quill had swiftly realized that only they could see this building, that passers-by were looking at his team searching the ruins as if they were performing some sort of avant-garde mime. They’d discovered a few details of a group that called itself the Continuing Projects Team, people who, they’d been startled to find, showed up not at all on internet searches. Quill’s team had already seen what a huge amount of energy it took to make one person be forgotten by a handful of people. The idea that a group of prominent people could be made to vanish so completely from public memory was staggering. They had found an empty personnel file that these people had kept, and on the cover of it had been the name ‘Detective Superintendent Lofthouse’, and then she had stepped from the shadows, holding an ancient key that Quill had recognized as having been on her charm bracelet. ‘This,’ she had said, ‘explains a lot.’

Quill and the others had been bursting with questions. She’d shaken her head in answer to all of them.

‘I know you lot are doing something… impossible,’ she’d said finally. ‘I realized that a while back.’

Quill had pointed at the key. ‘What does that have to do with this? Did you know the people who worked here?’

She had raised her hands to shut him down. ‘It’s only because you say so that I know there is something here. I can’t tell you anything more, James. I know less than you do.’ She’d asked for a detailed description of the ruins, walking through them with a look on her face that said she was willing herself to sense something there, but couldn’t. There was pain in that expression, Quill had realized. She’d handled the key as she’d looked around at what to her was just an empty area of Docklands pavement, reflexively toying with the object. Then, when she’d been satisfied that she’d been told everything, she’d looked once more to Quill. Her expression drew on their old friendship, hoping he’d understand. ‘I’m sorry,’ she’d said. ‘I know you want more from me. For now, please, just accept. Be certain you can always rely on me. From now on, tell me about your operations. I’ll believe you. But I can’t tell you why.’

Before they could say anything more, she’d marched off into the night.

Quill had understood at that moment that Ross had had that expression on her face that he’d come to associate with some immediate deduction or revelation. ‘Oh,’ she’d said. ‘Oh.’

‘That, from her,’ Costain said, ‘always ends with us getting told something true but deeply shitty.’

‘Even with the Sight,’ said Ross, ‘Jimmy still forgot his daughter. He couldn’t process any of the clues to her presence in the physical world. He just ignored them. So how come we can see that document listing the people who worked here, who otherwise have been completely forgotten?’ She hadn’t given them a moment to think about an answer. ‘For the same reason that these ruins have been left. Deliberately. For people like us, who can see things like this, to notice.’

‘As a sign, a warning,’ said Sefton, nodding urgently. ‘That’s why all we’ve found is a list of those people and nothing else. Having found that document, we now know it’s possible for people like these, people like us, to be not just killed, not just wiped out, but actually erased from everyone’s memories.’

‘It’s a display of power,’ said Costain.

‘She—’ Ross indicated where Lofthouse had gone—‘knows more about that situation than we do. But if we want to keep this unit going, we can’t ask her about it.’

‘“Just accept”,’ repeated Quill, sighing. ‘Does she know any coppers, do you think?’

In the three months since, they hadn’t found out anything further. DeSouza and Raymonde, the firm of architects that owned the land upon which the temple stood, when interviewed, had no more knowledge of the Continuing Projects Team than anyone else. Ross’ examination of the documents found at the scene revealed them to be mostly about architecture. She had shown the others what looked to be learned debates about how ‘the side of a building does turn the water’ written in a brown and curly hand that looked like something from the seventeenth century, and printed pamphlets from before that arguing lost causes in dense language. Those who’d curated this material seemed not to have understood it much more than Quill’s group did. There were only gestures in the direction of a filing system or index. Nor could they find any useful occult objects in the ruins. On closer examination it had become clear that, as Ross had speculated, scavengers had been through the place and taken anything useful.

Lofthouse had set up regular meetings between herself and Quill, and had listened with great interest to his reports of things which she should think impossible. True to his word, he had not asked her any questions. It meant that he left every such meeting feeling exactly as tense around her as he was feeling now.

He picked up his bacon sandwich for a last bite before they had to go and meet the man in charge of the Spatley case and glanced to his team, trying to keep the wryness out of his voice. ‘Good to have you onboard, ma’am,’ he said, ‘as always.’

Detective Chief Inspector Jason Forrest had a body like a rugby player’s, wore a bespoke suit and had an old scar down his left cheek. He looked as if he’d been persuaded at gunpoint to let Quill and Lofthouse into his office this morning. He asked a lot of questions about the exact purpose of Quill’s ‘special squad’ and rolled his eyes at the imprecise answers he received. ‘Come on, why should I ask you lot to help with my investigation?’

‘Because if there are features you find hard to explain—’ began Lofthouse.

‘How do you know that?’ He sounded bemused to the point of anger.

Lofthouse looked to Quill. Quill told him about Ross’ search strings.

The DCI’s expression grew even more nonplussed. ‘Why are you interested in words like “impossible”?’

Quill had his explanation prepared. ‘Following the Losley case, we’ve been specializing in crimes with an occult element to the motive.’ The look on Forrest’s face suggested that Quill was barking up the right tree. ‘We’ve been given access to… advanced sensor… techniques, the details of which we can’t go into. It gives us a bit of an edge.’

‘You jammy buggers. We could do with that technology for the riots.’

‘We’re trying it out. Maybe other units will get it soon.’ ’Cos you’d really enjoy that.

Forrest considered for a moment longer, looked again to Lofthouse and finally gave in. ‘All right, I’ll formally request that your team assist in the investigation. You’ll get access to the crime scene after it’s been forensicated, and to witness statements and evidence. I’ll be overjoyed for you to help out my very stretched staff by interviewing persons of interest. I’ve already lined up searches at Spatley’s offices, both in Whitehall and the Commons, but if you can think of anywhere else to search, I’ll okay that too.’

‘Thank you, sir,’ said Quill. It was already occurring to him that his lot would not need just to find different places to search, but to go over the same places, given their advantage of having the Sight.

‘So, here’s the problem.’ Forrest opened the file on his desk and placed some gruesome crime scene photos in front of Quill and Lofthouse. ‘We have a car surrounded by witnesses for the whole time frame in which a murder could have been committed. We have CCTV footage of that car throughout. We have enormous coverage of the incident on Twitter, loads of social media photos. No one gets in, no one gets out. One of the two men in the car is brutally murdered. The other maintains he didn’t do it. Incredibly, we have some reason to believe his account—because we can’t find the weapon. The driver, Tunstall, has some of Spatley’s DNA on him, but only what you’d expect from him getting in the back to try and help Spatley after the attack, as he told us he did. I suspect,’ he finished, looking up from the photos, ‘this may well be how the word “impossible” popped up.’

Quill was making a determined effort not to smile; his target nominal had appeared on the horizon. There was something in the photos that was literally shining out at him, which Forrest and Lofthouse could not see. His team had, brilliantly, finally, a case of their own. ‘Is there any chance, sir,’ he said, ‘that my team could take a look at that CCTV footage?’

‘This lot can’t work out what we’re about,’ said Costain, as a young female detective constable closed the door of an office behind Quill’s team and left them to it. ‘We could be an elite squad, we might be irrelevant. I got halfway to convincing that young officer of the former.’

‘You didn’t say a word to her,’ said Ross, switching on a PC.

‘It was how I walked.’

‘Oh, I’d let myself forget that for just a second. You’re such a people person.’

Costain’s front remained intact. ‘One of us has to be. But, being serious, thank you for noting that.’

Ross didn’t make eye contact with him as she set up the PC to view the footage. That holier-than-thou carefulness that Costain often adopted these days in his fear of going to Hell seemed to annoy her more than it did Quill and Sefton.

When it appeared onscreen, Quill’s team moved in close to see the images that might give them new purpose. Only Lofthouse held back. They were looking down on a car caught in a traffic jam, protestors swarming around it, some of them looking up at the camera and covering their faces further. A couple of bricks were thrown towards it, but nothing hit it, thank God. Many of the protestors were done up in that Toff mask and cape.

Then something different came walking through the crowd, approaching the car from the left. Quill’s team all leaned forward at the same moment.

The figure flowed past the protestors, its presence pushing them aside, its passing going unfelt.

‘That’s also someone in a Toff outfit,’ said Sefton.

It was. But it was blazing white, obviously a thing of the Sight. It was like watching an infrared image of a warm body in a cold room.

‘The trouble is,’ said Ross, ‘you can’t see much detail.’

Quill looked over his shoulder to check with Lofthouse.

‘I can’t see anything,’ she said. ‘Which I suppose is good news.’

He looked back to the image. The figure was pushing itself up against the side of the car, still getting no reaction from those around it. It started easing its way into the vehicle, until it had completely vanished inside. They watched for a few moments as nothing much happened, horribly aware of what had been reported, but seeing nothing through the tinted windows.

Suddenly, the figure burst out from the right-hand side of the car. It left a spatter of silver as it went. Quill recognized that stuff, whatever it was, as what he’d seen shining out of the car crime scene photos, a liquid that had been deposited all over the seats. With the grace of a dancer, the figure leaped onto the heads of the crowd, and then it was jumping into the air—

It was literally gone in a flash.

Quill’s team all looked at each other, excitement in their expressions.

‘Well?’ asked Lofthouse.

‘We have set eyes on our target nominal, ma’am.’

‘Excellent. I want to be kept in touch with all developments. As soon as possible, I want your proposed terms of reference for a new operation.’

Quill was sure his team would have applauded, if that was the sort of thing coppers did. For the first time in weeks, there was an eager look about them.

TWO

The torso of Michael Spatley MP was a horrifying mass of wounds, including an awful washed stump of pale, open blood vessels where his genitals had been hacked at.

‘He seems to have been slashed across the throat,’ said the pathologist, ‘and then multiple incisions across the abdomen, by a very sharp blade, probably that of a razor. The weapon was not found at the scene. His testicles were cut at their base and the subsequent shock and swift large loss of blood was the cause of death. Time of death tallies with the clock on the CCTV camera, which indicates between eighteen-thirty-two and eighteen-thirtynine. Direction of blood splatter—’ she held up a photo of the interior of the car from the files they’d all been given by DCI Forrest’s office—‘is consistent with the assailant kneeling across the rear seats. No arterial blood was tracked back to the front seats. The driver appears, and I stress appears, to have stayed put in the front during the attack.’

‘From other CCTV cameras,’ Ross noted, ‘it’s clear that the brake lights come on at several points during the time the car was stuck there, meaning that someone’s foot was still on the brake pedal, until a point which may coincide with the driver going to help the victim after the attack, as per his story.’

Quill knew from what only his team could see that that was actually precisely true.

‘How interesting,’ said the pathologist. ‘Not my department.’

What she wasn’t talking about, because she couldn’t see it, was what Quill could see the others glancing at too. All over the corpse, from the grimace on his face to the ripped-up abdomen, there lay traces of the same shining silver substance they’d seen earlier. It looked like spiders’ webs on a dewy morning, or, and Quill stifled an awkward smile at the thought, cum. As the pathologist went into a more vigorous description of how the wounds had been inflicted—frantic slashing and then precise surgical cuts—he gave Costain the nod.

Costain suddenly spasmed in the direction of the pathologist, knocking her clipboard from her hands, as if he was on the verge of vomiting.

Sefton quickly took a phial from his bag and, while the pathologist was fussing over Costain, managed to get enough of the silver stuff into it. He screwed the top closed and dropped it back into the bag.

The pathologist was helping Costain straighten up. ‘If you’re going to do that, we need to get you out of here,’ she was saying.

‘No, no,’ Costain waved her away and abruptly straightened up, smiling at her as he handed her back the clipboard. ‘Thanks, but I think I can hold it.’

They went to the custody suite and arranged an interview with Spatley’s driver. Brian Tunstall looked stunned, Quill thought, stressed out beyond the ability to show it, as if at any moment this would all be revealed as an enormous practical joke at his expense. He must be somewhere on the lower end of the Sighted spectrum—there were degrees to this stuff—because he hadn’t mentally translated what he’d seen into something explicable. But Quill supposed that, in the circumstances, doing that would have been quite an ask. There were still traces of the shiny substance on his shirt. It was odd to see an adult standing with such mess on him, not seeing it, and therefore not having attempted to clean himself up.

‘Listen,’ Tunstall said immediately. ‘I want to change my statement.’

‘Now, wait—’ began Quill.

‘What I said happened was impossible. It couldn’t have gone like that, could it? One of the protestors must have got into the car—’

‘Mate,’ said Costain, ‘we believe you.’

Tunstall stopped short. ‘You what?’ Then he slumped, a tremendous weight on him again. ‘Oh, right, I get it: you’re the good cop.’

Costain pointed to himself, looking surprised. ‘Bad cop.’

‘Surreal cop,’ said Sefton, also pointing to himself.

‘Good cop,’ admitted Quill. ‘Relatively. Which is weird.’

Ross just raised an eyebrow.

Tunstall looked between them, unsure if they were taking the piss.

Being interviewed by this unit, thought Quill, must sometimes seem like being interrogated by Monty Python’s Flying Circus. At least they had his attention. ‘Why don’t you tell us all of it,’ he said gently, ‘just the truth, as you saw it, and don’t edit yourself for something that’s too mad, because mad is what we do.’

Tunstall sat down at the interview table. ‘What does that mean?’

‘We have access to… certain abilities that other units don’t. Which means that, as Detective Sergeant Costain says, we are indeed willing to believe you. We know there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio. So telling the whole truth now might really do you a favour.’

The man looked more scared than ever.

It took until lunchtime to complete the interview and sort out the paper work. Tunstall’s stor y was indeed impossible, and confirmed all the physical evidence. The man finally said he couldn’t remember anything else and needed to get some sleep. Quill ended the interview. He found his own attention starting to wander and baulked at the prospect of going back to the team’s nick for maybe only an hour or two of bleary discussion, so he sent his team home for the day and went back to his bed. Only to find that Jessica was home and wanted to play with trains. So that was what they did, until Quill lay his head down on top of the toy station and started snoring.

Kev Sefton felt that he was finally getting somewhere. Being the officer who’d become most interested in the London occult and who’d started to read up on it had given him some extra responsibilities, okay. But now, instead of being second undercover, he was first… whatever his new job title was. Doing that well made him feel better about being out of the mainstream of policing while London was going up in flames.

He’d kept the phial with the silver goo in it in his fridge at home overnight, next to the beer, with a Post-it note on it that told Joe not to touch it. That summed up, he thought, the make-do way his team did things. He was used to having odd dreams now, as his brain dealt with all that he’d had to stuff into it, but those of last night were particularly weird. He felt as if he’d been rifled through and shaken out, as if large things were moving inside him. That phrase had brought a smile to his face as he drove through the gate that led onto the waste ground across the road from Gipsy Hill police station, the mud baked into dust by the early sunshine. No change there, then. He’d stopped on the steps of the Portakabin that served the team, exiled from the mainstream as they were, as an ops room and looked out across London. There was that smell on the warm air… smoke. Well, now they might be doing something to help restore order. He’d taken a deep breath and headed inside.

Now, as the others watched, wearing oven gloves he’d stolen from the canteen across the way, he was using a pencil to encourage the silver goo out of the phial and onto a saucer. He was hoping that graphite and tea-stained china didn’t react with whatever this silver stuff was. Maybe it would tell them something if it did. He was trying to take a scientific approach to his London occultism. Sometimes that made him feel like Isaac bloody Newton, and sometimes as if he was barking up completely the wrong tree. It felt as if this London business only submitted to science sometimes, when it felt like it. The goo dropped onto the saucer. The others leaned closer. Sefton thought he could hear a faint sizzling. He took the thermometer he’d bought at the chemist’s and held it as close to the gel as he dared. He nodded and put on his most serious expression. ‘It’s… really cold,’ he said.

‘Like the insides of every ghost we’ve encountered,’ said Quill.

‘Only this is much more extreme, and, because we’re pretty sure that what we’ve seen aren’t exactly ghosts in the usual sense of the word, inverted commas around the g-word, please,’ said Sefton.

‘Is that it’s “really cold” the full extent of your analysis?’ asked Quill.

‘If we can get hold of some specialist tools, like maybe a temperature sensor that I could actually risk inside this stuff, then I’d do better. But that’d only get us so far. Only we can see this material. It’s too plastic for mercury, too metallic for some sort of oil by-product, and it’s keeping itself and the things around it cold, like a fridge, but without being plugged into a socket. If it’s an element, it’s one we’ve discovered.’

‘Seftonium,’ said Costain.

Sefton used a teaspoon to put the goo back in the phial. ‘So-called spirit mediums used to pretend to be able to project something they called ectoplasm, which usually turned out to be glue and other gunk. Maybe the original idea for that came from this.’

‘Like in Ghostbusters,’ said Costain.

‘It reminds me of what I saw inside those “ghost ships” on the Thames,’ said Ross. ‘They had a sort of silver skeleton inside.’

Quill went to the corkboard which served this team as an Ops Board. ‘All right,’ he said, ‘we’ve got enough to start building the board, to list the objectives and to name this mother.’ All the board still had on it—the artefacts of the other half-arsed would-be operations they’d considered lately having already been consigned carefully to drawers—was the PRO-FIT facial description picture of the Smiling Man and the concepts list, which now was just a series of headings referring to files on their ancient computer (and the phone number of the Smiling Man, which Quill had labelled ‘the number of the Beast’). At the very top of the board was a card with a question mark on it, over which Quill now pinned a new blank card because the name of the operation was about to be decided. Beneath all that Quill added a picture cut from a newspaper. ‘The victim: Michael Anthony Spatley, Liberal Democrat MP for the constituency of Cheadle. Chief secretary to the Treasury, which is a cabinet position. Jewish by birth, atheist by inclination. Forty-six years old. Wife: Ann. Daughter: Jocelyn. Son: Arthur. I’ve put in a request for us to search his home and offices too, which, judging by the tone of voice of the PA I spoke to, will be regarded with incredulity by those who’ve already had the main op through. But we shall persist.’ He attached a red victim thread upwards from the picture and pinned a sheet of white paper above it, on which he drew a very rough cartoon of the Toff figure.

Ross took a new square of paper and added ‘Brian Tunstall’ to the suspect area, also attaching a victim thread between him and Spatley. She drew a dotted line beside both threads, indicating uncertainty. ‘Two suspects,’ she said.

‘Despite the fact that only one of these “suspects” was observed fleeing the scene,’ noted Costain.

‘Yeah, because we make assumptions only when the specialized nature of our work forces us to. And then we take care to note them.’

Sefton looked between the two of them. Costain had always been the sort of officer who’d insisted on the importance of first-hand street experience, and Ross’ intelligence-based approach always felt that that procedure was missing the wood for the trees, but now… He knew that Costain, when Ross had been unconscious in hospital after the Losley case, had stayed by her bed, had slept in a chair. Sefton had wondered, during those few weeks when Ross had been full of the joys of spring, if they were going to get together. That looked impossible now, which was tough on these two, because he and Quill had someone to talk to about the impossible stresses this team were under, and they didn’t.

Costain picked up a card of his own and drew a squiggly mass of people on it, then he attached it to Spatley with a dotted thread too. ‘Maybe it’s the “spirit” of the riots? Losley said there were two ways to power in London: to “make sacrifice” or “be remembered”, and it’s not like it’s only the old or famous stuff that gets remembered. We hadn’t heard of that green monster thing Kev met. Maybe this is the sort of collective will of those protestors made solid, or something.’

Quill nodded. ‘Good. But I hope that doesn’t bloody turn out to be the case, ’cos it’s going to be hard to nick a manifestation of the collective unconscious.’

Sefton had something to add. ‘All the “ghosts”’—he made the speech marks gesture—‘we’ve seen have been really passive. Everything “remembered” as part of what seems to be a sort of collective memory on the part of London just kind of hangs around, in classic haunting fashion. They didn’t hurt anyone. Not even the remembered versions of Losley.’

‘So maybe one of the protestors has made a sacrifice and is deliberately making this happen,’ said Costain.

‘Absolutely.’ Sefton was glad to hear Costain making deductions like that about his world. Sefton couldn’t do this bit alone, and it always pleased him when the others had a go. He was the opposite to Ross in that respect because his speciality was bloody terrifying and hers wasn’t. ‘But Losley was very set in her ways and didn’t acknowledge things she didn’t approve of or know about. She didn’t mention various powerful items, for instance, like the vanes that were used to attack Jimmy. I don’t think we should imagine she knew or was telling us about every mechanism that exists to do… the sort of stuff we know objects that are very London can do. Speaking of which…’ He stepped forward and added, down the left-hand side of the board, in the space which their team and only their team used for concepts, ‘Cold residuals. Meaning that silver goo.’

‘But which now sounds like something you’d need to talk to your agent about,’ said Quill.

‘Nobody outside the car saw anything,’ said Ross. ‘Nobody felt the suspect move through or above the crowd. Tunstall’s testimony is what you’d expect of someone who was watching an attack by an invisible assailant. And I should add…’ She used her own pen to write ‘Can walk through walls (slowly)’ under the cartoon of the prime suspect.

‘Like Losley,’ said Costain.

She also added ‘Can vanish’.

‘And again.’

‘Remind me to cover that up at the end of the day,’ said Quill. ‘We don’t want to terrify the cleaners.’ He paused as he stepped back from what was once again a blankness. ‘We need to do proper police work on what’s up there,’ he said. ‘We need to find meaning, a narrative. We work our three suspects: in the real world and in what, horribly, I’m starting to think of as our world.’

Sefton saw that now was the time to announce the plan he’d been putting together. He was a bit proud of this, the sort of cross-discipline package that, in normal police work, would have been a boost to his CV. Now Lofthouse had made it obvious that she was aware of what they did—whatever the implications of that were—it might still be a good career move. ‘I’ve been assembling a list of people who seem to be on the fringes of the subculture we encountered at that New Age fair. I know a few places where they hang out. I could start to attempt undercover contact, get some sources for general background on all this stuff and work towards specifics concerning the Spatley case, if you think it’s time to risk all that.’

‘I do.’ Quill nodded. ‘Go forth and make it so, my son.’ He turned back to the wall and began pinning up a big sheet of paper on the right of the board. ‘And now, ladies and gentlemen, it’s time for… operational objectives!’ He picked up a marker and began to write.

- Ensure the safety of the public.

- Gather evidence of offences.

- Identify and trace subject or subjects involved (if any).

- Identify means to arrest subject or subjects.

- Arrest subject or subjects.

- Bring to trial/destroy.

- Clear those not involved of all charges.

‘Maybe it’s a bit vague,’ he admitted, standing back to admire his work, ‘but for us it’s always going to be. Even writing the word “destroy”…’ He let himself trail off. ‘But that’s how it is for us. And, of course, this list mirrors the objectives of Forrest’s SCD 1 murder inquiry, which, if we’re not careful, may lead to conflict and ire. Now, instead of drawing the names from the central register, I say we continue to name our own ops because that’s how we roll and I like it. So for this one, where we might well be venturing into Gothic and clichéd portrayals of our fair metropolis, how about…’

He wrote on the card at the top of the Ops Board:

OPERATION FOG

The rest of the day was spent assembling all the evidence they had and building their initial Ops Board to the point where they all felt they were looking at everything they knew. They kept the news on in the background, but no fresh details came to light in the press. Ross had set up a bunch of hashtag searches on Twitter, but, as the day went on, they only revealed that London was panicking and gossiping in many different ways about the murder; no one signal was poking up out of the terrified noise.

All in all, Sefton was glad to have put in such a productive day and, with the Portakabin getting stuffy, he was pleased when Quill sent everyone home. Home was now a tiny flat above a shop in Walthamstow with, on good nights, a parking space outside. Tonight he was lucky. The flat was half the size of the place he’d used as an undercover. It was like suddenly being a student again. Joe, who lived in a bigger place, had started coming over and staying most nights, which neither of them had commented on, so that was probably okay. Tonight he found Joe had just got in, using the key Sefton had had made for him two weeks ago, and was planning on heading straight out to the chippy. ‘Best news all day,’ Sefton said, after kissing him, and they headed off.

The streets of Walthamstow were full of people, loads of office workers coming out of the tube in shirtsleeves, jackets slung over their shoulder, women pulling their straps down to get some sun. They looked as if they were deliberately trying to be relaxed, despite the smell of smoke always on the air, even out here. But even the sunshine had felt sick this summer, never quite burning through the clouds, instead shafting through gaps in them. It felt as if the whole summer was going to be dog days. Or perhaps all that was just the perspective of the Sight. It was impossible for Sefton to separate himself from it now. Every day in the street he saw the same horrors the others did, startling adjuncts to reality. ‘The opposite of miracles,’ he’d called them when Joe had asked for a description. There was a homeless person begging at the tube entrance as the two of them passed, an addict by the look of him, thin hair in patches, his head on his chest, filthy blankets around his legs. He was newly arrived with the ‘austerity measures’.

‘So,’ said Joe, ‘what did you do at work today?’

‘Can’t tell you.’

‘I thought you told me everything.’

‘Everything about the… you know, the weird shit. Nothing about operational stuff.’

‘Ah, so now there is operational stuff.’

‘Yeah. Kind of big, actually.’

‘Oh. Oh! You mean like what everyone’s been talking about all day?’

Sefton sighed. Why had he been so obvious? ‘And now I’m shagging a detective.’

Joe worked in PR for an academic publishing house and was now doing the job of what had been a whole department. His work stories were about dull professors who couldn’t be made interesting.

He lowered his voice. ‘I saw about the murder on telly and thought the same as everyone else is saying, that it had to be the driver—’

‘I can’t—’

‘—which means it must really be something only you lot can see, like, bloody hell, another witch or something, like maybe there’s one for every football club? The witch of Woolwich Arsenal? The witch of Wolves? It can only be the alliterative ones. Liverpool doesn’t have one. Liverpool has a… lich. Whatever one of those is.’

Sefton put a hand on his arm and actually stopped him. ‘Could we just get those chips?’

They sat on the low wall of the car park outside the chippy and breathed in the smell of frying. The old woman in a hijab they always saw around here trod slowly past, selling the Big Issue. Sefton bought one.

‘How are your team getting on now?’

‘I can’t talk about the case.’

‘Which is why I’m asking about the people.’

‘I think there’s something up with Ross.’

‘Really?’ Joe followed the people Sefton talked about as if they were characters on TV, never having met them, and Sefton almost laughed at the interest in his voice.

‘Ever since she got into the Docklands documents, she’s kind of suddenly gone back to how she was: all curled up against the world. Maybe it’s that she’s found something terrible and doesn’t want the rest of us to have to deal. Maybe she’s waiting until she’s got all the details.’

‘Like what?’

‘I don’t know. I don’t even know if she and Costain are rubbing each other up the wrong way or…’

‘Just rubbing each other?’

‘I hope it’s that. It’s weird when I get a feeling about a person now. I’m trying to let myself be aware of the Sight all the time, to listen to something whispering in my ear, but, doing that, you start to wonder what’s the Sight and what’s just you. If I’m not careful I’m going to start being like one of those toddlers that notices a bit of gum on the pavement and hasn’t seen that before, so he squats down and keeps looking at it until his mum goes, “Erm, no—big wide world, more important.” The others want me to keep looking into the London occult shit, to be that specialist, and, you know, I like that responsibility, but they don’t really get that that kind of leads you away from being a police officer. Crime stories: all about getting everything back to normal. This stuff: there is no normal.’

‘Crime stories say the centre can hold; in reality, it’s going to fall apart any minute. Maybe all this chaos lately is something to do with the sort of thing you lot investigate.’

‘Yeah, we’re all wondering about that: that maybe the shittiness of life right now is all down to the Smiler and how he’s “moved the goalposts” and changed London. That’d be a comforting thought, eh?’

‘Only for you is that comforting.’ Joe, having finished his own, took one of Sefton’s chips. ‘I think the riots and protests would have happened anyway. The protestors are the only people left who give a shit. You just expect a sort of… self-serving hypocrisy from politicians now. You’d be amazed what the guys in my office said about Spatley. Nobody was like, “He deserved it,” but…’ He let the sentence fall away with a shrug.

Sefton let his gaze drift along the street full of people. ‘Bloody general public. Even with London falling apart in the world they can see, all they talk about is the royal baby and The X Factor and all that shit—’

‘You like The X Factor.’

‘—while my lot are involved with… the secret of eternal life, making space out of nothing, extra “boroughs” that don’t seem to be in this universe. You know what’d be really good?’

‘Go on.’

‘You remember when I caught that “ghost bus” and went… somewhere else, somewhere away from this world, and talked to… whatever that being was, that called himself Brutus and dressed like a Roman?’

‘You really told your workmates about this?’

‘I really did, but even when I did it sounded like something I’d dreamed or made up. Anyway, just having met some sort of… big London being… that the others hadn’t, I felt like I’d started to get a handle on this stuff. But as time goes on I’m starting to feel more and more that I did dream him. It’s not as if he gave me much in the way of solid advice, a path I could follow. He didn’t leave me with anything certain, with any mission in life. And without that certainty, there’s this… gap. There’s all sorts of stuff I want to ask him about. I’ve made an actual list, and today I added the silver goo to that list.’ He rubbed the bridge of his nose and then had to brush away the salt from his chips he’d deposited there. ‘Sometimes I feel like he might just show up, that I might sit down on a park bench and there he’d be. And then there are times when I know he isn’t real. You can sort of feel something like him in the air, sometimes.’ He was very aware of Joe’s arched eyebrow. ‘You can. That’s a proper Sighted feeling. That seemed to be getting easier as summer came on, but now…’

‘When Ross got her Tarot cards read, she was promised “hope in summer”, wasn’t she, and “in autumn” too, just those sentences? And it had something to do with that card called “The Sacrifice of Tyburn Tree” which you all thought was about her dad—’

‘You remember all the details, don’t you? You’re such a fanboy of us lot. Just don’t go on the internet with this stuff.’

‘I’m saying, maybe good stuff is about to happen. Maybe you’ll find Brutus.’

Sefton sighed, had to look away from that smile. ‘But it’s summer now, and it’s just this… burdened heat.’

‘Is there anything you can do to, you know, summon him or something?’

‘Nothing in any of the books I’ve found. He’s not in the books. If I can’t find him, I need to find… something.’ Sefton suddenly felt the need to get rid of all this shit. ‘Fuck it, I need a pint. And you’re not going to let me go on about the Hogwarts stuff any more tonight. Deal?’

‘No,’ said Joe, smiling at him.

As always, Lisa Ross was awake into the early hours. Hers was one of many lights still on in her Catford housing block. There were people who kept a light on at all hours, no matter what the bills were, as if that offered some protection against the shrieks of the urban foxes and the drunken yelling outside. She barely registered that stuff. She would get the three hours’ sleep she found necessary sometime around 3 a.m.

Tonight, like every night, she was about her secret work. She was sure that the others thought she was nobly sacrificing her spare time to make a database of the documents they’d found in the Docklands ruins. She had let them think that. It was safer. Quill had stars in his eyes about her, about her having saved his daughter. She was letting him and the rest of the team down so badly.

But she had no choice. After the ruins had been looted for so long, there hadn’t been much of interest left, so she wasn’t actually keeping the team from anything that could help them. She wasn’t telling them the whole truth either. The document she spent all her time on now was about her own needs. It had probably been spared the scavenging that had emptied that building because it was written in an indecipherable language in a hand that didn’t invite study. That obscurity had spoken to her of something being deliberately hidden. She had found something like the script on a visit to the British Library archives. It turned out that it had been noted on only one tomb in Iran, but the inscriptions on that tomb had been written in several other languages also. So there was, it had turned out, printed only in one issue of one archaeological journal, and still not available online, a working alphabet for the document she had before her. It hadn’t taken her long to translate the document, and thus understand what she was looking at. The document was a description of an object that had arrived in Britain in the last five years, just before the destruction of the Docklands site, in fact. Now she was looking on her laptop at a series of objects that might prove to be that thing. She had been doing this for the last week of long nights. She was on the fiftieth page of the third such catalogue site she had visited, and she was still absolutely certain, because she made herself stay awake and alert at every page load, that she hadn’t yet seen the object she was after. She was starting to wonder if the tomb in question really had, as the document alleged, been empty. If there really was an object that would do what the document said it did.

There was a noise from beside her. A text message. She was startled to see it was from Costain. He was wondering if she ‘had five minutes’.

What? At this time in the morning? He’d never texted her before. He was probably drunk. Or was this meaningful? Was this the start of the sort of activity on his part that she’d told herself to watch out for? Whatever. She put the phone back down without replying.

Costain was the one from whom she especially needed to keep this work secret.

Quill was once again hauled awake by the sound of his phone. His dreams had been full of something reaching towards him, reaching into him. But he couldn’t remember it now. Jessica, unwoken by the sound of the phone, was lying across his head.

‘Would you please answer that,’ said Sarah, ‘and tell them to—’ she looked at her daughter and gritted her teeth—‘go away?’

Quill saw that the call was again from Ross, and said so.

‘Getting over her now,’ said Sarah.

He picked it up. After listening for a few moments, he quickly got out of bed and started getting dressed.

‘What?’ moaned Sarah.

‘Another one. It’s police.’

The slightly portly middle-aged man lay across the sofa. He was still dressed in a blue towelling robe, the now-familiar silver fluid splattered across him and all over the room. The robe was open, and so was he. A livid red trail led from what remained of his abdomen, across the polished wooden floor, and finished in an explosion of blood against the far wall, next to a Jack Vettriano. The expression on the victim’s face was an almost comical extreme of horror and incredulity. His eyes were open, glassy.

Quill’s team stood in the doorway, feeling—if Quill himself was anything to go by—like anything but an elite unit at this hour of the morning. Forensics had just finished with the crime scene and were packing up. Uniforms were filling just about every available inch of the building.

What they were staring at was enormous. Bigger, even, than the death of a cabinet minister.

‘Sir Geoffrey Staunce, KCBE, commissioner of the Metropolitan Police,’ said Ross, keeping her voice low as a uniform made her way past.

‘They got him,’ said Quill. ‘That’s what the papers are going to say tomorrow. With a strike looming, the protestors killed London’s most senior copper at his home in Piccadilly.’

‘There were indeed Toffs in the area last night, making a nuisance of themselves,’ said Ross, looking up from the report she’d been given on entering. ‘For this sort of address that’s pretty incredible.’

‘The connection is also the locked room and the MO,’ said Quill.

‘Plus, from our point of view, the silver goo,’ added Sefton.

‘And,’ said Costain, ‘the wife is talking about an invisible assailant.’

They paused for a moment, taking in the scene. Quill’s team’s speciality was now being tested against a very mainstream, very high-profile, series of murders.

‘This is going to set London on fire,’ said Costain. ‘I mean literally.’

‘Where’s this message they were talking about?’ Stepping carefully, Ross followed the trail of blood across the room. She got to the enormous splatter of it across the far wall and stopped. Quill and the others joined her. She was pointing at the fine detail that the chaotic enormity of the splatter concealed. Among the blood was written, in awkward, blocky characters:

THE JEWS ARE THE MEN WHO WILL NOT BE BLAMED FOR ANYTHING.

‘What is that?’ said Sefton. ‘I recognize that.’ He started to tap at his phone.

‘So this is almost certainly from the killer,’ said Costain, ‘but—’

‘Making assumptions,’ said Ross.

‘You said we could—’

‘Only when we remember to mark them as such. This is me doing that. Yes, it could be from the killer, but there might also have been person or persons unknown here, associated with the killer or otherwise, who might have left what they regarded as a useful, or just anti-Semitic, message for the many Londoners who will read it when they get a news camera in here.’

‘Next time you make an assumption, I’ll make sure I mark it.’

‘I hope you will.’

‘Would you just bloody finish the sentence you originally started?’ Quill asked Costain.

‘Just that it’s really weird,’ said Costain, ‘to use “are the men” in what’s otherwise a natural-sounding phrase. It feels like… pretence to me. A front.’

‘You’d know,’ said Ross.

‘I would. There’s the fingerprint.’ He pointed to the very end of the words, where the fingers that had daubed the message had paused for just a moment, leaving a single smeared print.

Ross took a photograph of it. ‘I’ll ask to hear from the investigation about the comparison of that to the prints found in Spatley’s car.’

‘Oh, my God,’ said Sefton. ‘“The Jews are the men”!’ He held up his phone as the others clustered around. He read from it, keeping his voice down so the uniforms all around couldn’t hear. ‘Those words, or something like them, were what was written on a wall in a place called Goulston Street in Whitechapel, in 1888.’

‘So?’

‘It’s the message left by Jack the Ripper.’

The Severed Streets © Paul Cornell, 2014